ADVERTISEMENTS:

The early history of Central Asia is largely obscure and only faint glimpses of its cultural patterns prior to Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century B.C. can be had through ritual songs and legends of the nomadic tribes. The ancient Greeks and later, the Arabs were familiar with the area and its inhabitants.

The territory between the Amu Darya (the Oxus of the Greeks) and the Syr Darya (the Jaxartes of the Greeks) was known to the Arabs as the Jahun-Sayhun region which contained the sites of the famed urban centers such as Bukhara and Samarkand during the medieval times.

Islam came to the region with the Arab conquest in the mid-7th century and became firmly rooted by the 11th century when the Turks were ruling over most of Central Asia. The area from Kazakhstan to Turkmenistan then came to be known as Turkistan. Except for the Tajiks, who are the descendants of the Iranian peoples since the first-millennium B.C. and were ruled by them when the Turks had established over Central Asia, all the groups had adopted Turkic languages. Only the Tajiks remained linguistically distinct as speakers of Persian-related tongues.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The most notable event of the medieval times was the conquests of the Mongols who established an extensive empire under Genghiz Khan in the 13th century. The present-day distribution of ethnic groups was probably formed during and after the collapse of the Mongols Empire. The Russian encroachment in Central Asia started in the mid-19th century, first in the Kazakh territory and later in the area that lay south of it, gradually annexing all of Central Asia between 1840 and 1870.

The post-revolutionary period of the Soviet occupation after 1921 was marked by large-scale economic transformation of the land. Railroad links were forged with other parts of the Soviet Union; land reforms were enacted; and modernization of agriculture introduced, all accomplished with Russian technology and finances. In an exuberant burst of agricultural developments of their “Virgin Lands,” however, the focus appeared misplaced. The whole of Central Asian lands were galvanized to produce primarily cotton, an emphasis that proved ecologically disastrous.

The Russian decision to propagate agriculture in the “Virgin Lands” was also accompanied by a large-scale migration of Russian farmers into these new agricultural colonies, many of them later on moved to the newly emerging urban centers. The native tribal groups meanwhile took to sedentary occupation in the agricultural lands. The indigenous tribal population became slowly a minority in the urban centers. Most Central Asian cities now contain non-local population in large numbers; the Russians obviously dominate and form disproportionately high percentages in industry, and transport sectors.

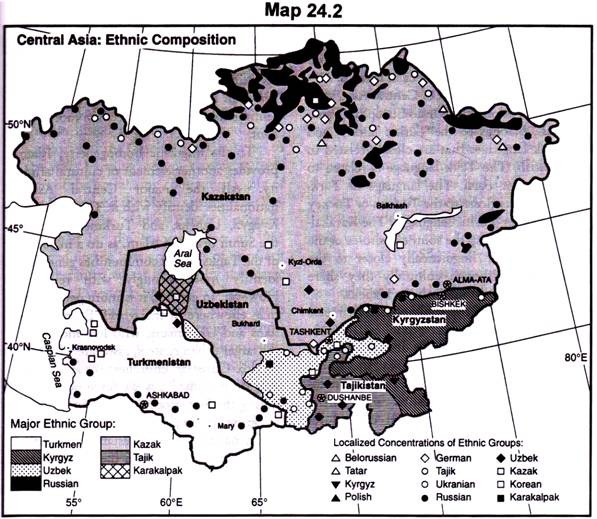

The five largest ethnic groups in Central Asia, in descending order of size, are the Uzbeks, Kazaks, Tajiks, Kyrgyz, and Turkmen, each residing within the republic that bears its name. (For example, Tajiks in Tajikistan; Uzbeks in Uzbekistan, etc.) The sixth group of the Karakalpakstans occupies a territory in the Amu Darya plain and has a subordinate political status within Uzbekistan.

The incorporation of Central Asia into Fascist Russia in the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries and later the Soviet Union, and the immigration of large numbers of several groups—including Russians, Ukrainians, Jews, Germans and Koreans— gave a distinctive multi-ethnic character to the cultural geography of Central Asia.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Predictably, the Russians rank second to the indigenous groups within each country, heir proportion of the total population varying greatly—from 35 percent in Kazakstan and 16 percent in Krygyzstan to a significantly lower level of 6 percent in Uzbekistan.

Prior to 1980, they formed a majority in Kazakstan, but have since experienced a substantial decline as did other non-indigenous groups such as the Ukrainians, Germans and Koreans. For the last three decades the indigenous groups have experienced proportionate gains in numbers, arising primarily out of their much higher rates of natural increase, but also from an increased out-migration of Russians.

All of the Central Asian nations contain substantial ethnic minorities, consisting largely of other indigenous ethnic groups reflecting their shared cultural and historic development, and also of the several non- indigenous groups, such as the Russians, Ukrainians, Germans, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the case of Kazakhstan, which contains the largest proportion of non-indigenous population, for example, the Russians account for over one-third of its population, the Germans, Tartars and others nearly a quarter, leaving the Kazaks in a position of a narrow majority.

Similarly, nearly a quarter of Tajikistan is composed of the Uzbeks, and so closely are the Tajiks and the Uzbeks intermixed that the Soviet partition of the area in 1924 failed to segregate them. The political boundaries demarcated by the Soviets in the mid-and-late 1920s, therefore, could not produce ethnic homogeneity.

Map 24.2 shows the ethnic composition in the five Central Asian nations.

Linguistically, all of Central Asia, with the exception of the Indo-European Tajikistan, belongs to the Turkic family, and speak languages that are closely related to Turkish. The Tajik language is related to Persian or Farsi. The language of Turkmenistan is closer to the Turkish of Turkey than other Turkic languages. The Karakal- pas, living along the southern shores of the Aral Sea are linguistically closer to the Kazakhs, although culturally they share common traditions with the Uzbeks.

In view of the multi-ethnic character of the Central Asian republics, Russian, Ukrainian, and German are spoken as a second language primarily by the ethnic Russians, Ukrainians or Germans. The introduction of Russian as an “official language” during the Soviet control remained primarily a language of the administration, and of the urban elite.

As Russian was made compulsory in schools, it was considered essential for advancement in workplace and was adopted by those living in large cities who acquired a working knowledge of it but a vast majority did not accept it. Recent trends indicate that the gains made through linguistic “Russification” in Central Asia may be reversed in the near future as the nationalist sentiments are likely to become more strident.

To the linguistic homogeneity, Islam provides another element of cultural affinity. All the major Central Asian nationalities identify with it. The Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Turkmen practice the Sunni brand of Islam, as do a majority of the Tajiks. Rural communities generally identify more strongly with religion. However, in general, it is more permissive than elsewhere in the world.

Ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, who live mostly in the larger urban centers, associate with Orthodox Christian churches. By and large, religion remained a weak force politically during the Soviet occupation, but is likely to grow in importance as the Central Asian nations begin to establish stronger regional connection with the neighboring Islamic countries such as Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia.